By Dr Helen Beattie, Managing Director, VAWA

The challenges in our use of animals and the environment are deeply intertwined and complex. Our so-called ‘wicked problems’ (such as intensive winter grazing and the lack of shade/shelter on many farms), need a considered, careful response – there is no single person, practice or policy that is the solution.

These practices negatively affect the welfare of people, animals, and the environment yet most of us have made little progress towards resolution. There are many interconnected and complex relationships within these scenarios, including financial bottom lines tied to mortgages and prosperity, and compromised environmental and animal welfare.

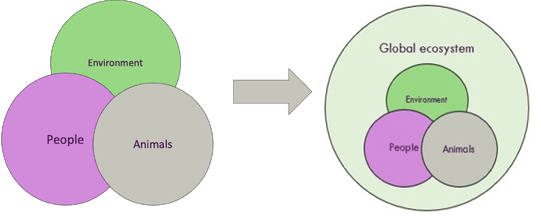

Systems thinking about the natural world’s entwined health and welfare is not new. Recently, the concepts of One Health, One Welfare have been championed as a way of thinking about this. Yet interconnectedness already runs deep through te ao Māori (the Māori world view).

Deferring back to this longstanding indigenous knowledge perhaps provides the next iteration of our thinking – a model where people, animals and the local environment are seen as parts within the wider ecological system, the welfare of which must be paramount. How we operate (i.e. our economy) must be constrained by the welfare of the finite world in which we live.

Fig 1. From One Health/One Welfare to an alternative conceptual model for welfare

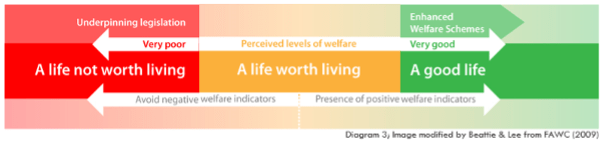

Our thinking has evolved to understand that health is a subset of welfare (i.e. healthy chickens in cages don’t have good welfare). Perhaps it might also progress from welfare to wellbeing, or perhaps further to ‘mauri’ (life spark/essence). On the image below, this would mean existing within the green zone which enables thriving and flourishing, and not merely surviving in the red or orange zones. While this relates to animals, the concept can be applied to Papatūānuku and people.

A siloed approach to policy and farming systems can hamper progress towards the end goal of profitable farming that provides animals with A Good Life,[1] and has an ecological footprint that is inside Papatūānuku’s capabilities. To have genuinely useful and long-lasting responses to our wicked problems, we need systems thinking, modified human behaviour and fair and just change. That would support successful outcomes for animals, people and our environment, and result in a thriving Aotearoa New Zealand.

[1] ‘A Good Life’ is one where animals live a life that has, on balance, more positive than negative experiences that are well above the legal minimum.